The Sunday Man

“I can be changed by what happens to me. But I refuse to be reduced by it.” — Maya Angelou

“Beneath the rule of men entirely great, the pen is mightier than the sword.” — Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Richelieu (1839)

“Kathy, hey, can I talk to you?"

The orange blaze of morning light was creeping its way across the vast savannah floor.

“Sure. You think we might find a lion today?”

Our safari guide, Franz, mopped the sweat from his cheek, though I still found the air cool.

“This guy,” he said. “I have to ask. What are you and your husband doing with this...guy?”

“My friend Mal isn’t he amazing? We invited him to join us on safari; he’s our guest. Is there a problem?”

“Look, yeah…people were asking last night...”

“What are they asking? What are you asking?”

“Well, see, he’s, I mean, he’s...Look, where is he from?”

“Soweto.”

“Yeah…you don’t see people from townships on these safaris. Not like this.”

It was 2011, and the Rainbow Nation was still painted in black and white.

His words were stark. I quickly realised that safari spaces like this still quietly policed who belonged, and who didn’t. That Mal’s presence was questioned revealed the unspoken rules born of decades of segregation and inequality during apartheid. Historically, these safaris were predominantly for affluent white visitors. I hadn’t realised it was still this way in 2011.

I glanced across at the bodies assembled around the picnic table, sipping their strong black coffee.

Franz didn’t need to say it.

I had been naive not to expect this.

The Rainbow Nation had yet to cast its colours here.

“Hey, Mal!” I called. “Franz is asking how we met.”

“Ah,” Mal grinned. “My friend, tell him, tell him!”

“Tell everything?”

“Sure. Guys, this is Kathy, my best friend in the world. She saved my life." He laughed. "You tell it, Kathy.”

Franz folded his arms across his khaki green vest, gaze wide.

Six curious pairs of eyes primed for lion spotting diverted their stare, ears straining.

I had become the hunted.

“Mal is my longest friend. We met for the first time a few months ago—after writing letters to each other for nearly 20 years.”

Lifelines

We first started writing in 1992.

Mal had lost another appeal against his 1987 death sentence for a murder he did not commit. Another man had, by then, taken sole responsibility. Because he admitted guilt, his death sentence had since been commuted to life.

Mal remained in prison.

I had reached out to a letter-writing group supporting prisoners. At the same time, they were encouraging Mal not to give up hope and join. I was 19 when I wrote that first letter. Looking back, I cringe at some of my writing. Fair to say, I had no idea what I was doing!

“First of all, this is not a romantic thing. The group said to make that clear. So that is clear. I was happy to receive your first letter. To answer your questions, I am 19 years old and I have a son. When he starts school, I intend to study criminology. I want to help.I think it is an unjust outrage what is happening to you.Please end your fast to death. You have to live.The apartheid system is so terribly wrong you must continue to fight it.In case you were wondering, I have no money to give you, but I can write letters. I read that 'The pen is mightier than the sword.' So, we must write. If you promise to live, we will let all the world know your name.”“Greetings to you. I hope you are well looked after. I have received your first letter. Thank you for writing back to me. It did make me laugh. Know that I have now started to eat again. I will be happy for us to be friends. You should also know there are some things you can’t talk about. They cut out banned words from letters. You will work it out.”

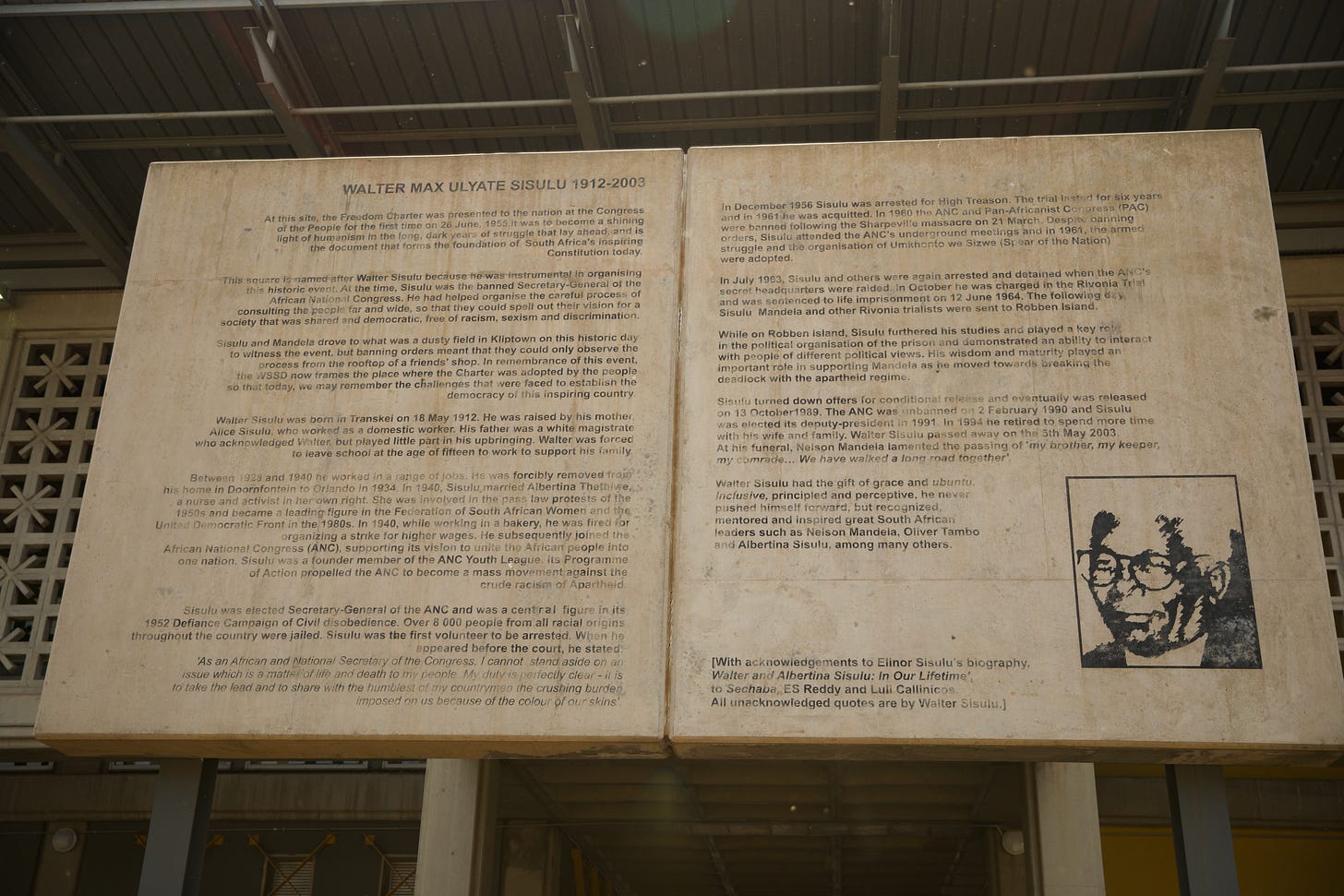

Supported by the ANC and his union, Mal claimed injustice and later political prisoner status. He had admitted taking part in an organised wage strike on the day of the murder, but maintained his innocence of any crime.

All I knew of Apartheid, I had learned from watching Cry Freedom on VHS. But I spent hours in the library collecting books. I wrote letters to every department in the South African government I could find until, finally, I received a reply from President de Klerk, acknowledging me as Mal’s representative. He had begun to make the first steps of reform that would lead to the dismantling of apartheid.

I remember Mal phoning in delight that he, too, had been informed I was his representative. The responsibility felt terrifying. What did that mean? Surely his fate was not going to lie only with me! Nevertheless, my writing had transcended borders and was joining a bigger movement. It actually might be making a difference.

The power of persistence felt mildly victorious. Yet for Mal, nothing much changed.

Until 1994.

“We thank you for your continued support and representation of the above-named prisoner. Please be informed that his death sentence has now been commuted to life imprisonment.”— Office of President Mandela (August 1994).

I ran my fingers across the name—Nelson Mandela. After all these years, the letter I had been waiting for had finally come. I was astounded.

The jubilation was short-lived.

A new fight was to begin.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was coming (1995-1996).

Mal’s plight was about to get worse.

The TRC offered freedom—but only to those who confessed. Mal could not give them what they wanted. He had nothing to confess to. For months, I feared the very hope I’d offered had become another sentence he couldn’t escape. If I hadn’t been so damn stubborn, might he be free now?

“Mum, it’s the Sunday man on the phone.”

“But, are you sure, Mal?” I had pleaded.

“I will not lie to be free, Kathy. Not for them. They can’t take my mind. We’ll fight this.”

For fifteen years more, we fought—writing, waiting, refusing to give up.

Seasons flow continually, tumbling in and out, with us or without us.

As a young single parent in the 1990s, I knew how it felt to be abandoned by society when you had done nothing wrong. Mal told people I saved him. I told him he saved me. I sent packages to his children—dolls, soccer boots, and later school supplies. I sent clothes and books to Mal. Maya Angelou became his favourite.

I got married.

Had another child.

Moved house.

Completed years of study with the Open University. Every criminology course I could find.

Writing, learning, writing—to no avail.

Mal stayed in his small cell.

It was Christmas Eve 2009. The kitchen was full of the annual bustle. My eldest son, home from uni, was making cookies with his younger brother.

“Kathleen, it’s Mal on the phone,” my husband called.

“Mal, hi, hey, my big brother, how are you?”

“Kathy, my sisi, we did it. I am standing here outside, and I am free. We did it, Kathy!”

We laughed and cried. And then cried and laughed.

After 22 years, without notice or ceremony, Mal walked free.

“It always seems impossible until it’s done.” — Nelson Mandela

Later, in 2010, when we visited the prison together after his release, the prison warden met us at the gates.

“You,” the prison warden yelled. “It’s you! The one with all those damn letters. Every time you wrote, they would phone me—so many phone calls. So I would ask Mal. What does this woman want?”

Mal grinned. “And I say to you, boss, she just wants my freedom. She won’t stop!”

They both laughed in a way that had never occurred to me. Over the years, they had become friends.

I used to worry I was interfering in something I didn’t fully understand. But Mal never saw it that way. For him, the letters were a reminder he hadn’t been forgotten.

We walked through the prison together, the Warden leading the way.

"Hey, guys, it's Kathy from Scotland!" Mal said.

They—knew—me.

"You know it's that story", one prisoner said. "You drop a stone in the water and all the ripples came here, to us."

The warden glared. “Don’t even think of helping anyone else, or I’ll have you out now!”

A new dawn

“Guys, we are done for this morning, yes?” Franz lowered his gaze.

A resounding yes echoed—then silence as the white faces climbed back aboard the safari jeep.

“Mal”, an American called out, “Why Sunday man?”

“I phoned Kathy every Sunday morning. If her son answered, he would shout out, Hey mum, it’s the Sunday man!”

Mal beamed. “That's my family—in Scotland.”

Later, Franz found me waiting by the braai. He walked forward, head lowered.

“I didn’t know, I…Do you know what they did to people in Pretoria Max-C prison? How did he survive the torture?”

“I told Mal the pen was mightier than the sword. I dunno…I was young. Anyway, he believed me. He just kept on believing the letters would work.”

Looking back now, I wonder—I hope—that over these years, the rainbow has spread more widely.